Surgical care in the United States today is less likely to involve hospital admission than it was 20 years ago. Some researchers estimate that 70% of all surgical procedures in the United States are now performed in an ambulatory setting—either a hospital outpatient department (HOPD), a freestanding ambulatory surgery center (ASC), or a physician office.1 The transition away from inpatient settings has been accompanied by concerns about the impact on the quality and the cost of care. Medicare payment rates for a given outpatient surgical procedure are different for an HOPD (usually highest), an ASC, and a physician office (usually lowest), and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has issued recommendations to better align payment across these different settings.2 Commercial payers have similar discordant payment policies. Clinical outcomes by site of service are less well understood, and there are few recent studies of contemporary patterns in the specialty of urology. Hollingsworth et al3 examined a set of urologic procedures commonly performed in the ambulatory setting between 1998 and 2006 and concluded that fewer complications occurred in the ASC setting but that same-day hospital admissions were more common for the ASC setting than the HOPD setting. Many more major urologic procedures have shifted to the ambulatory setting in the 12 years since this paper was published,4 and there are now safety and reliability data on some procedures.5 This study sought to describe the outcomes and relative cost by site of service for urologic procedures commonly performed in ambulatory settings today.

Summary of Main Points

- Many urologic procedures can be performed in either an office setting, an ASC, or an HOPD. The majority of common procedures performed by community urologists are done in the most expensive setting: an HOPD. This large study suggests that the physician office or ASC is both a safer and a less expensive setting for common outpatient urologic procedures than the HOPD.

- Policymakers can use this information to align different payment systems and provide financial incentives to use safer and less expensive sites of service for these common procedures.

Abbreviations

ASC ambulatory surgery center

ED emergency department

HOPD hospital outpatient department

OR odds ratio

Methods

This retrospective study of anonymized claims did not constitute human subjects research, nor did it violate any human subject protections; informed consent was not sought from patients. Data for the study came from LUGPA, whose members contribute practice management data extracted from their billing systems (ie, claims data). The study and analysis are based on data from the completed claims of 2238 urology professionals in 41 practices for procedure dates of service from January 2022 to December 2023. A total of 16 procedures were selected for analysis primarily based on their rank order of frequency in the ambulatory setting; simple cystoscopy, vasectomy, and prostate biopsy were excluded from the final analysis because of wide interpractice variation in site of service and low incidence of outcomes of interest. The study included all transurethral procedures for benign prostatic hyperplasia because of an interest in outcomes by setting and in previous research in this area.5 Claims data from all financial classes and payers were included in the study, and the information was properly modified to prevent the identification of individual patients and clinicians. The principal unit of measure was a surgical episode that began on the date of service and lasted 90 days without regard to payer “global periods”; each occurrence of a triggering Current Procedural Terminology code generated a new episode, even if it occurred within another episode window.

To examine outcomes the study looked at 4 metrics (percentage of episodes with an event within 30 days of the procedure): (1) emergency department (ED) visits; (2) hospital visits (inpatient or outpatient); (3) urethral catheterizations; and (4) any encounter with the occurrence of 1 or more International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes denoting a complication (list of codes available by request). To analyze relative cost, the site-specific Medicare allowable charge for professional fees was first assigned to all services occurring within the 90-day episode (including the index Current Procedural Terminology date or day 0). Pathology services billed by urology professionals were excluded because we had no ability to compare costs when they were performed by other professionals at a facility. Facility fees for each episode were assigned using the Medicare Procedure Price Lookup for Outpatient Services software.6 Professional fees were cross-indexed to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician Fee Schedule.7 Our primary interest was in examining differences in outcomes and costs by ambulatory surgical setting. Covariates included patient attributes (index procedure, patient age, patient sex, financial class) and clinician attributes (sex, US Census region, years in practice, and practice size). To examine postoperative outcomes, univariate logistic regression models were constructed for each predictor and each of the 4 metrics of interest. A stepwise approach was then undertaken for a multivariate regression model, where all predictors were initially included in the model but were dropped unless they were significant (P < .05). For the regression model examining costs, the same process was undertaken, and a log transformation was performed on the costs as a result of the long tail in distribution stemming from episodes with high costs. The statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4, software (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

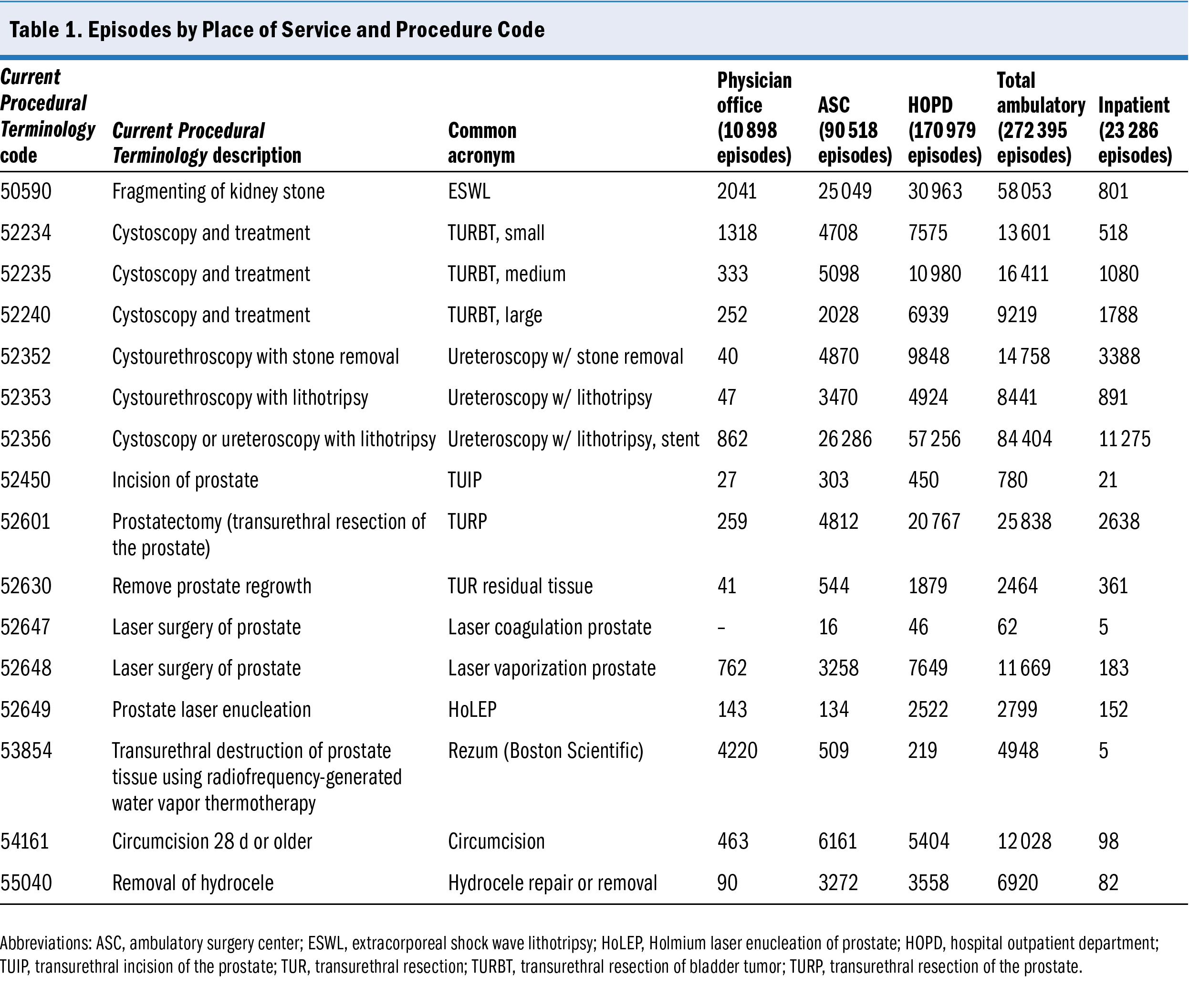

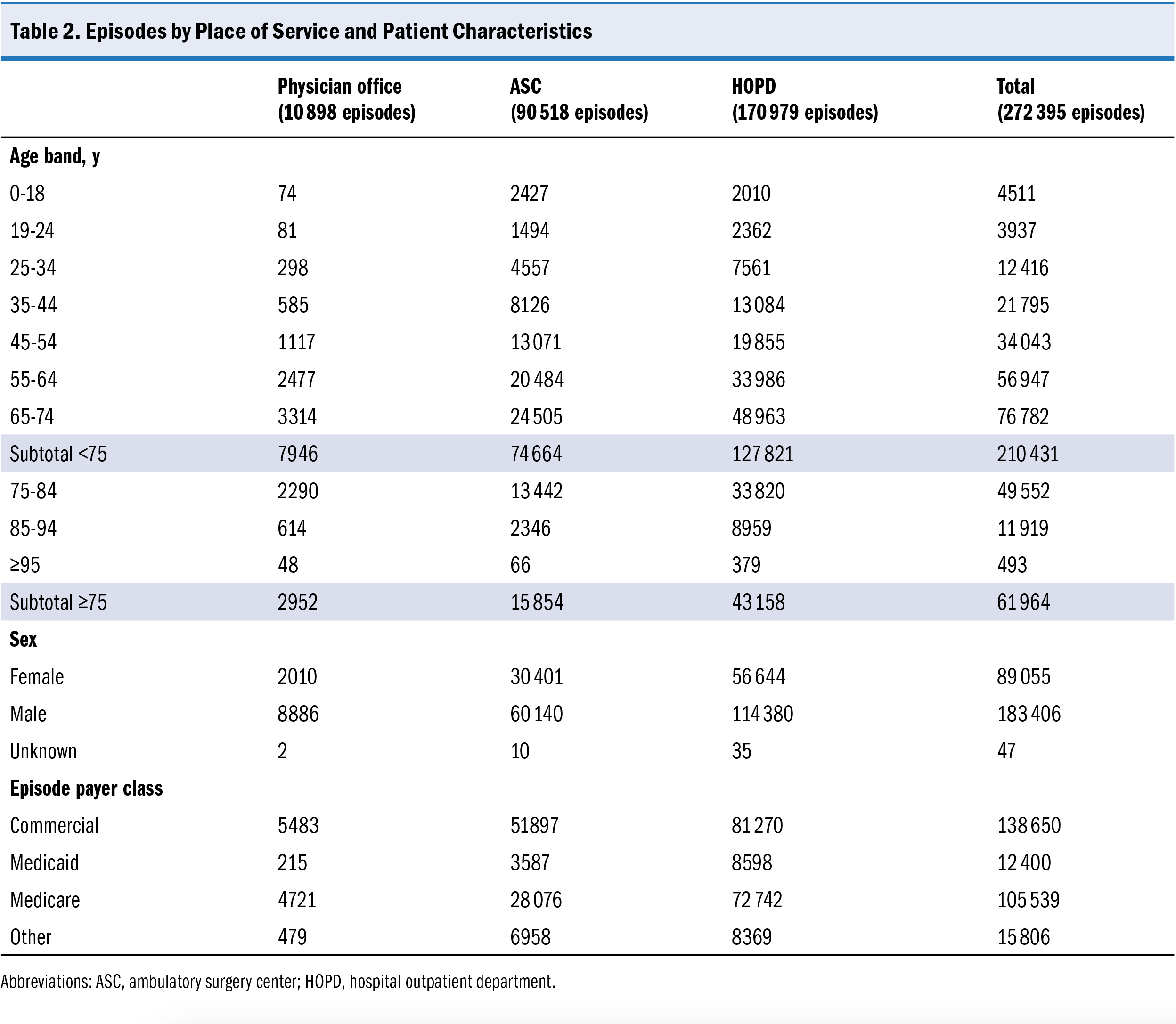

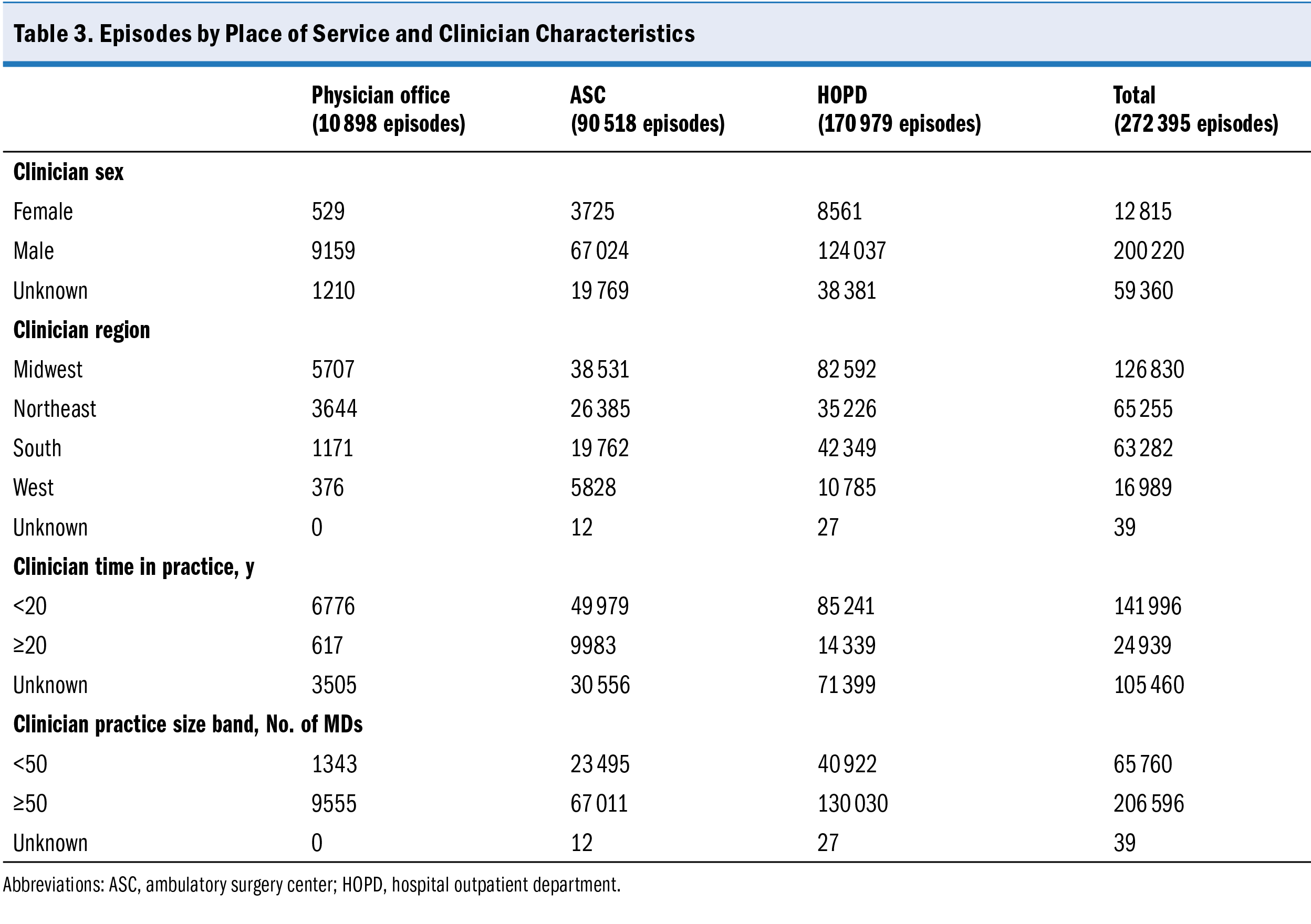

A total of 272 395 surgical episodes initiated in ambulatory settings were identified over the 2-year study period performed by 1162 unique health care professionals in 41 unique practices. Of this total, 170 979 procedures (62.8%) were performed in the HOPD, 90 518 procedures (33.2%) were performed in the ASC, and 10 898 procedures (4.0%) were performed in the physician office (Table 1). The most common procedures in the study were ureteroscopy with lithotripsy (31.0%) and shock wave lithotripsy (21.3%). Patients were predominantly younger than 75 years of age (77.3%), male (67.3%), and had commercial insurance (51%) or Medicare (35.8%) (Table 2). Clinician characteristics associated with the episodes are listed in Table 3. Most of the surgical procedures in this dataset originated in 18 practices, with more than 50 physicians (75.8%).

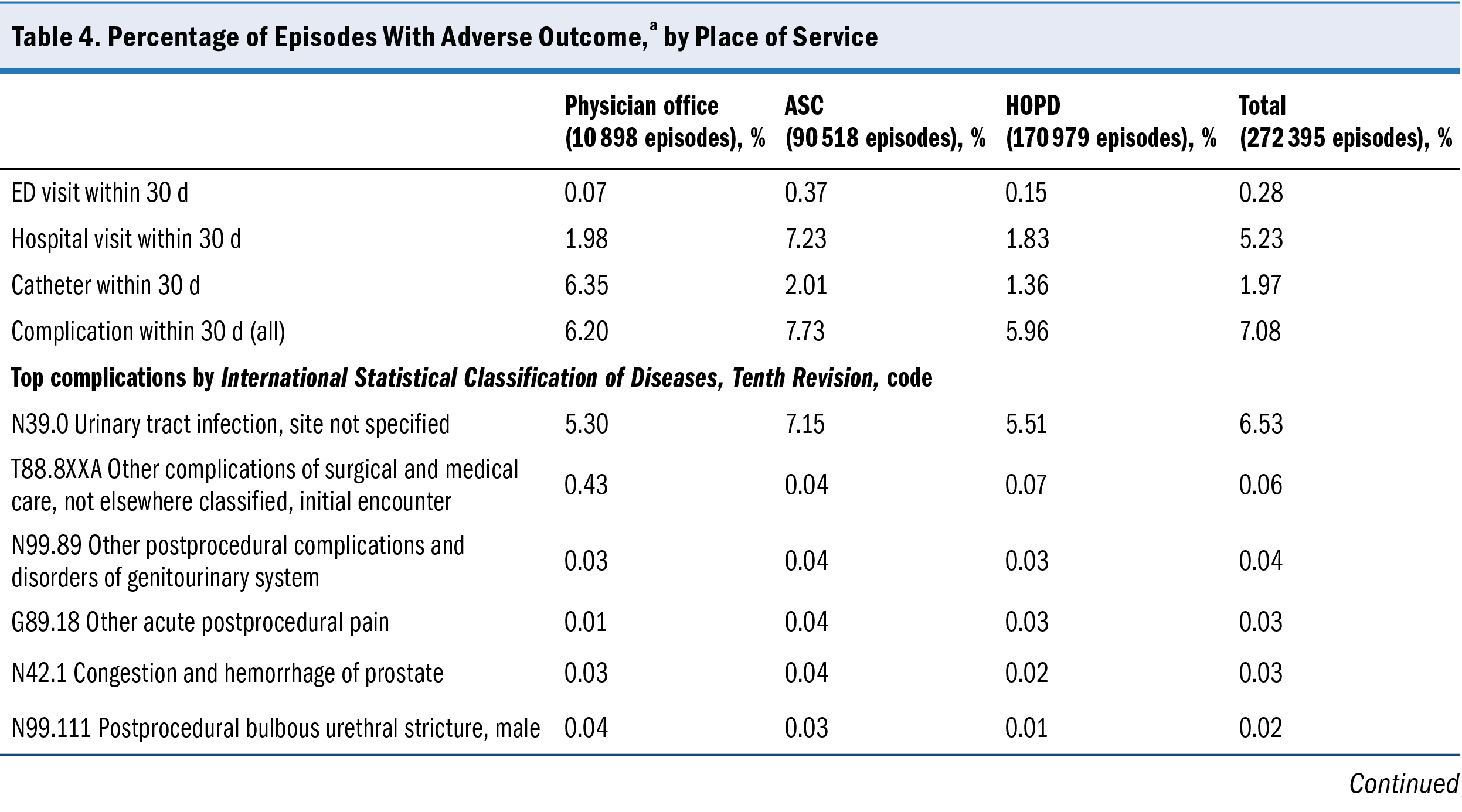

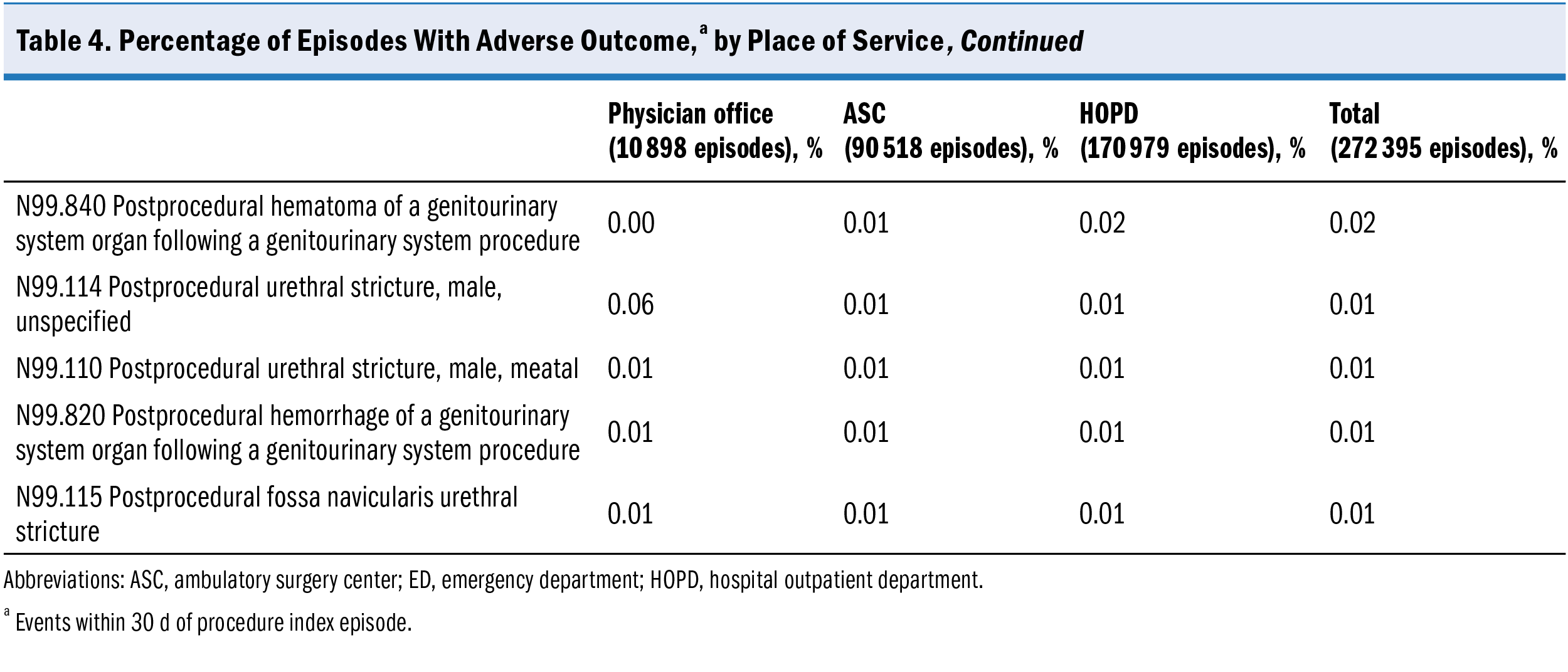

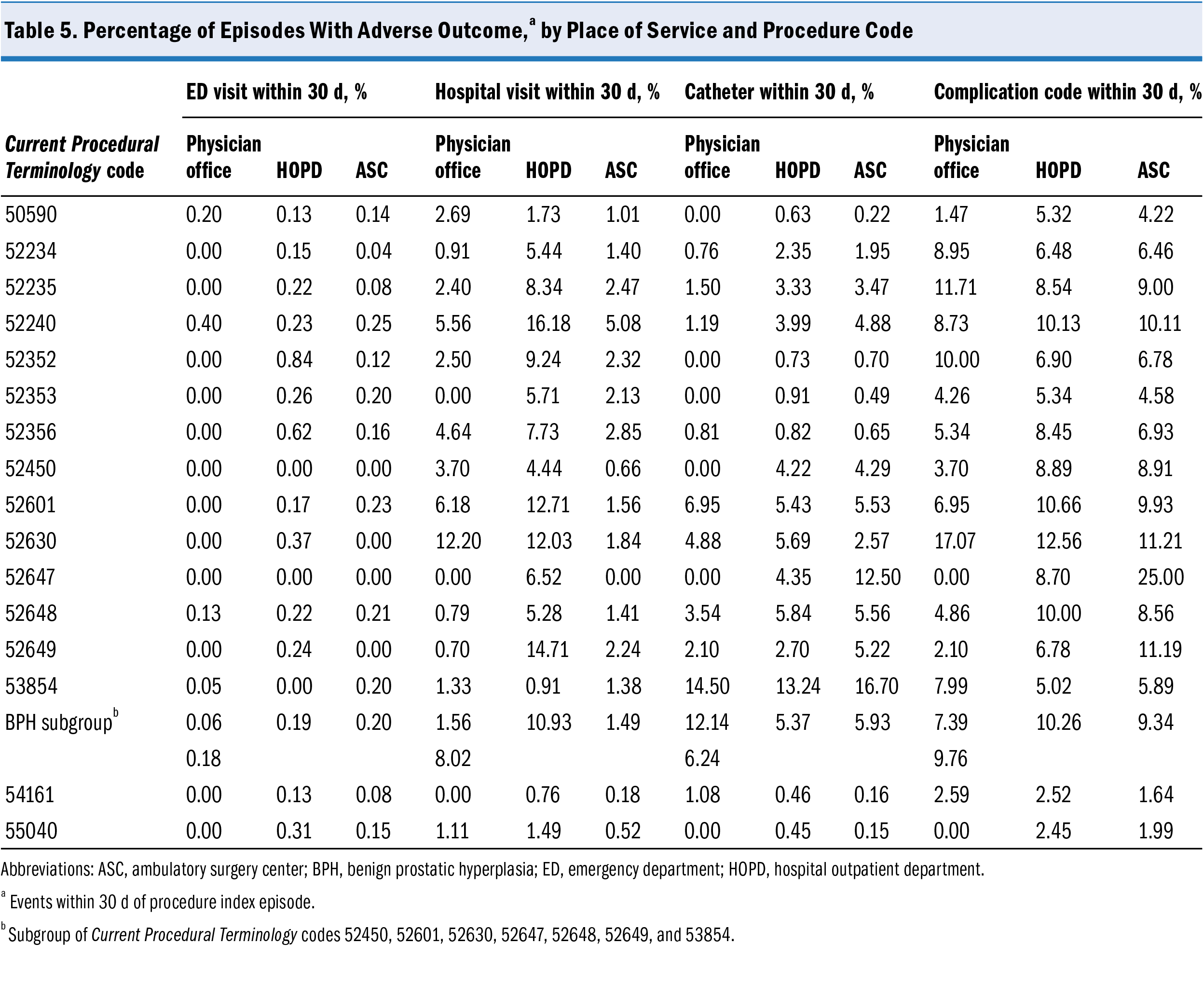

Outcomes are presented as a percentage of episodes in Table 4. Emergency department visits within 30 days of an ambulatory procedure occurred in 0.28% of all episodes, hospital visits in 5.23% of episodes, and catheterizations in 1.97% of episodes. A total of 7.08% of episodes had an encounter within 30 days of the procedure that included a complication code on the claim; the top 11 complications are listed in Table 4. Table 5 displays the information by procedure code.

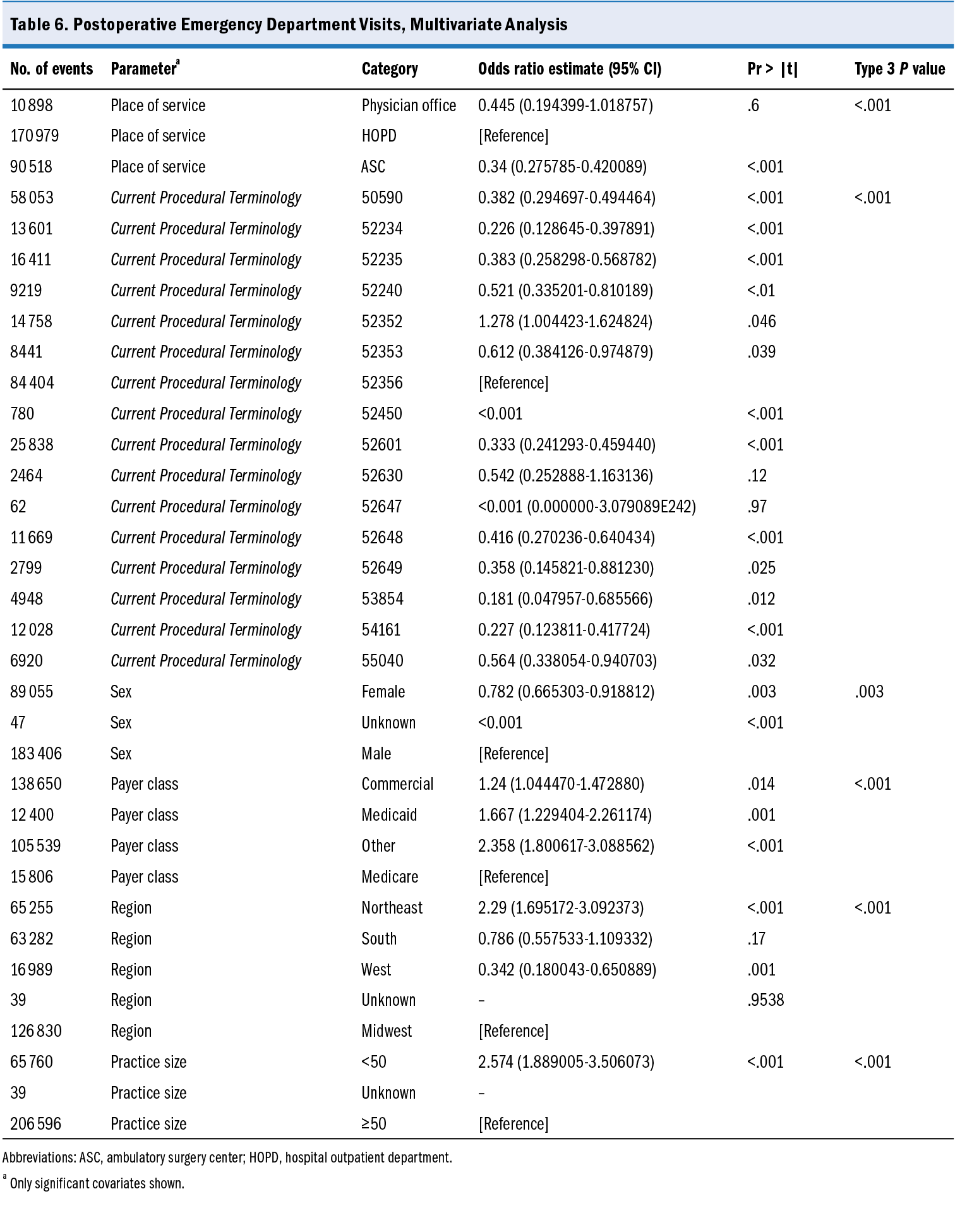

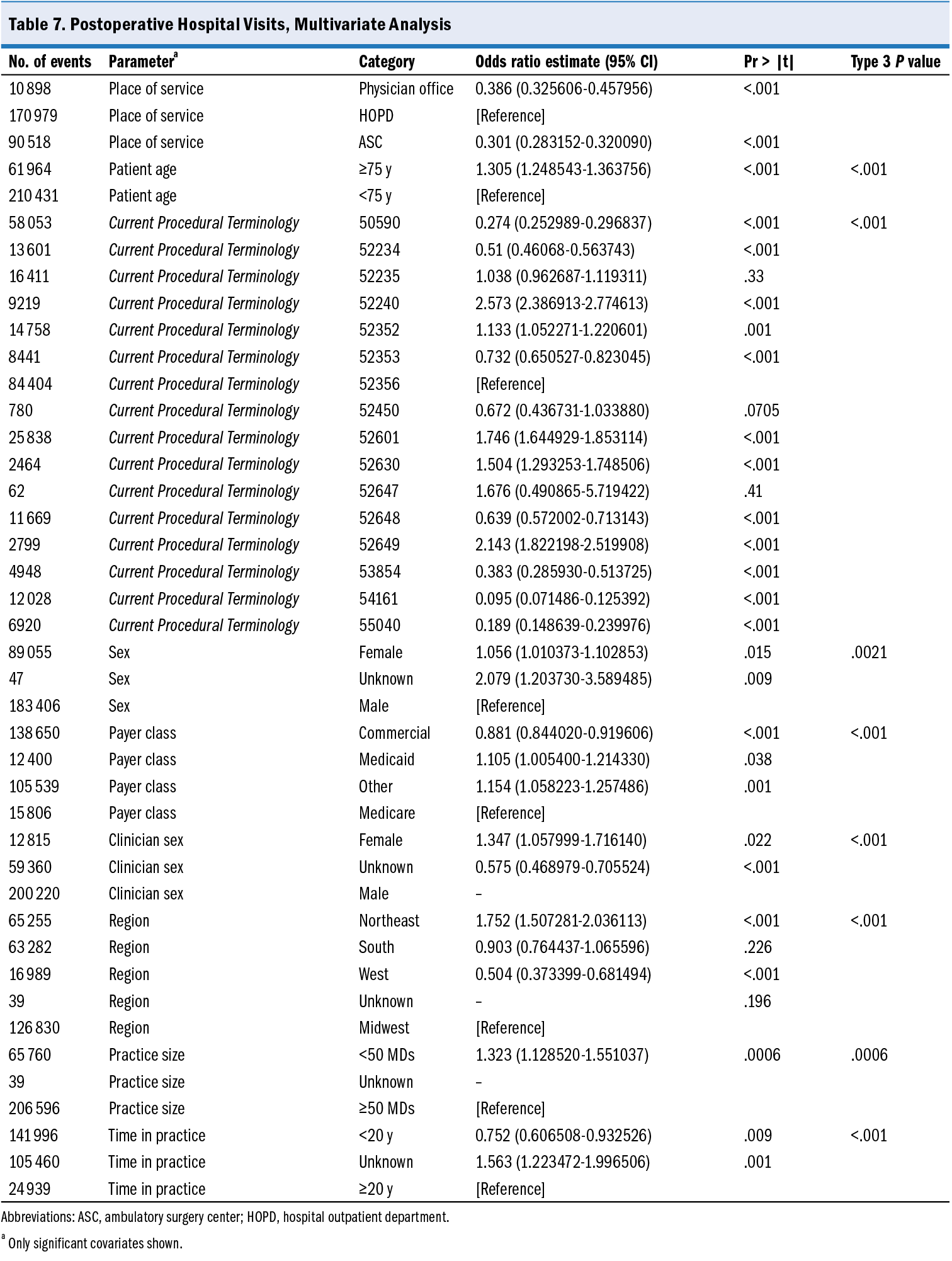

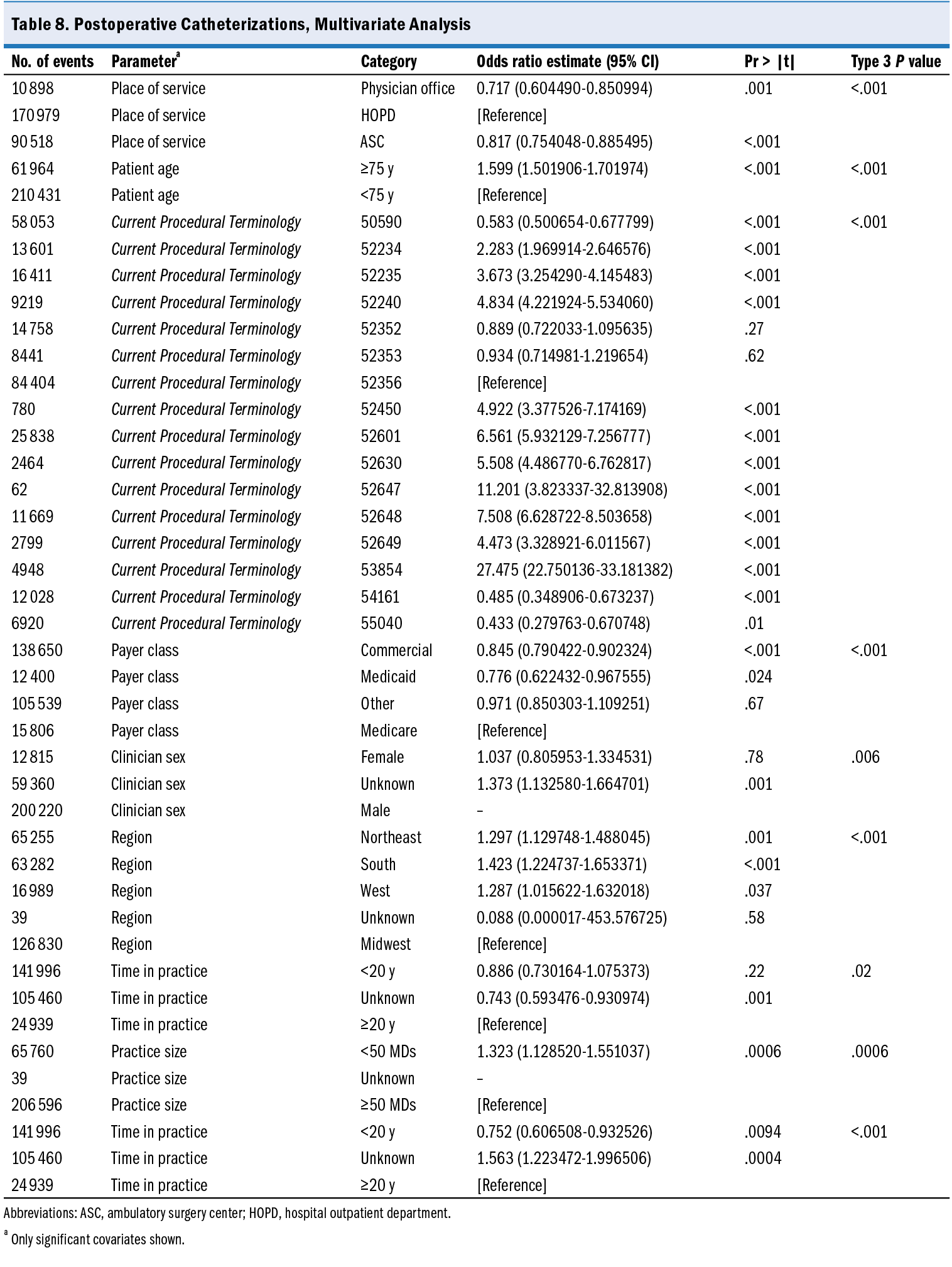

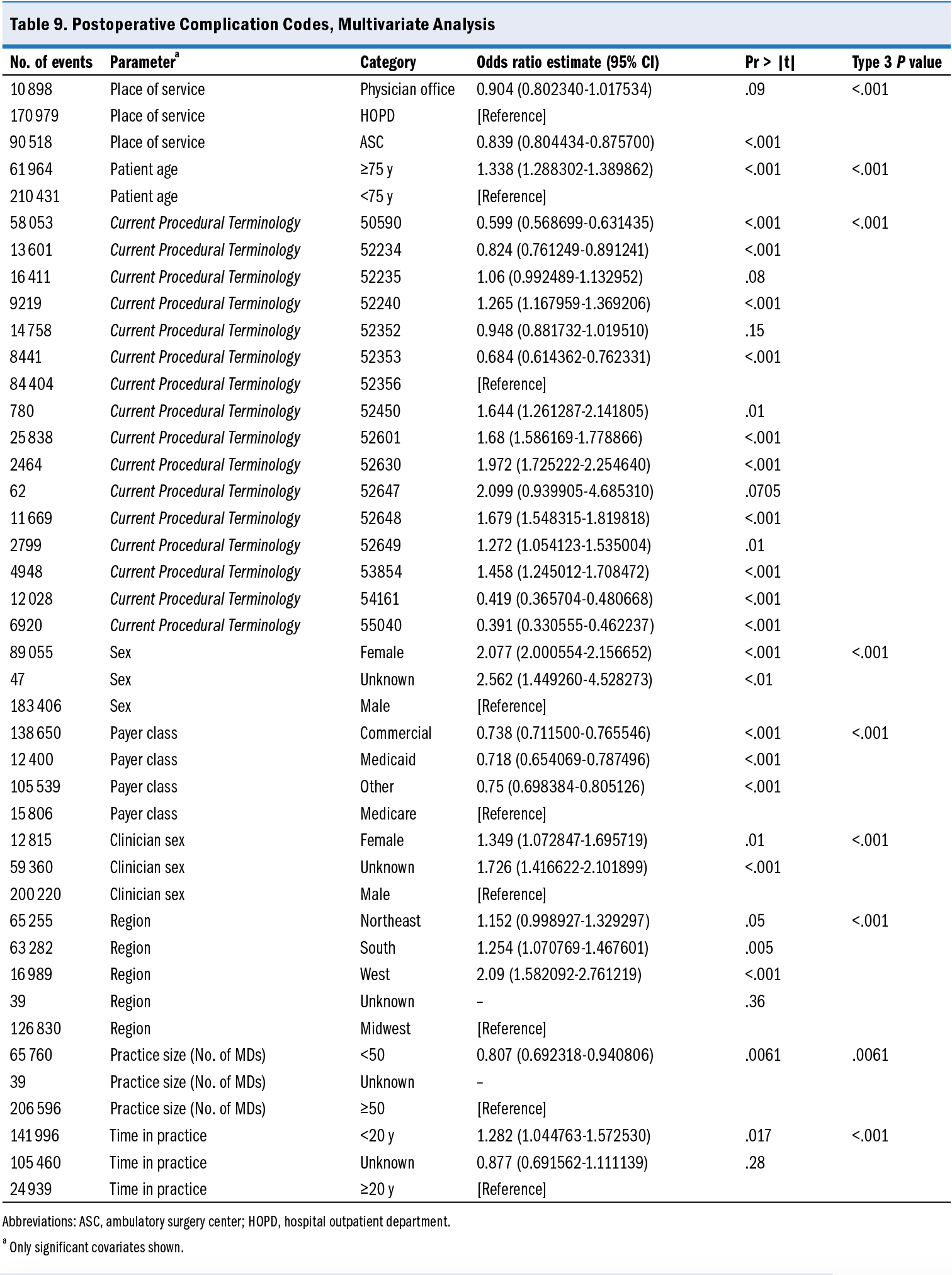

Multivariate analysis of the principal outcomes is displayed in Table 6 through Table 9. After controlling for other variables, ED visits within 30 days were significantly less likely after procedures performed in an ASC than in an HOPD (odds ratio [OR], 0.340;

P < .001), but there was no significant difference for this outcome between the physician office and the HOPD (OR, 0.445; P = .0567). Hospital visits within 30 days were less frequent in the ASC setting (OR, 0.301; P < .001) and in the physician office (OR, 0.386; P < .001) than in the HOPD. Postoperative catheterizations were also significantly less frequent after procedures in the nonhospital settings (ASC OR, 0.817; P < .001; physician office OR, 0.717; P < .001) than in the HOPD. Finally, the odds of having a complication code assigned to an encounter within 30 days of a procedure was significantly less likely for procedures done in an ASC (OR, 0.839; P < .001) compared with an HOPD; differences between physician offices and HOPDs for this outcome were not significant (OR, 0.904; P = .0943).

There were other statistically significant predictors of outcomes in this study as well as some inconsistencies. After controlling for other variables, ED visits were not significantly different by patient age group, but the other 3 outcomes were significantly more common in patients aged 75 years and older (P < .001). Female patients were less likely to have an ED visit (OR, 0.782; P =. 0.0028) but more likely to have a hospital visit (OR, 1.056; P = 0.0154) and more than twice as likely to have a complication diagnosis code (OR, 2.077; P < .001) than male patients. Commercially insured patients were more likely to have an ED visit (OR, 1.24; P = 0.0140) but less likely to have a hospital visit (OR, 0.881; P < .001), catheterization (OR, 0.845; P < .001), or complication diagnosis (OR, 0.738; P < .001) than were patients insured by Medicare. Similarly significant but inconsistent findings were seen in clinician and practice characteristics.

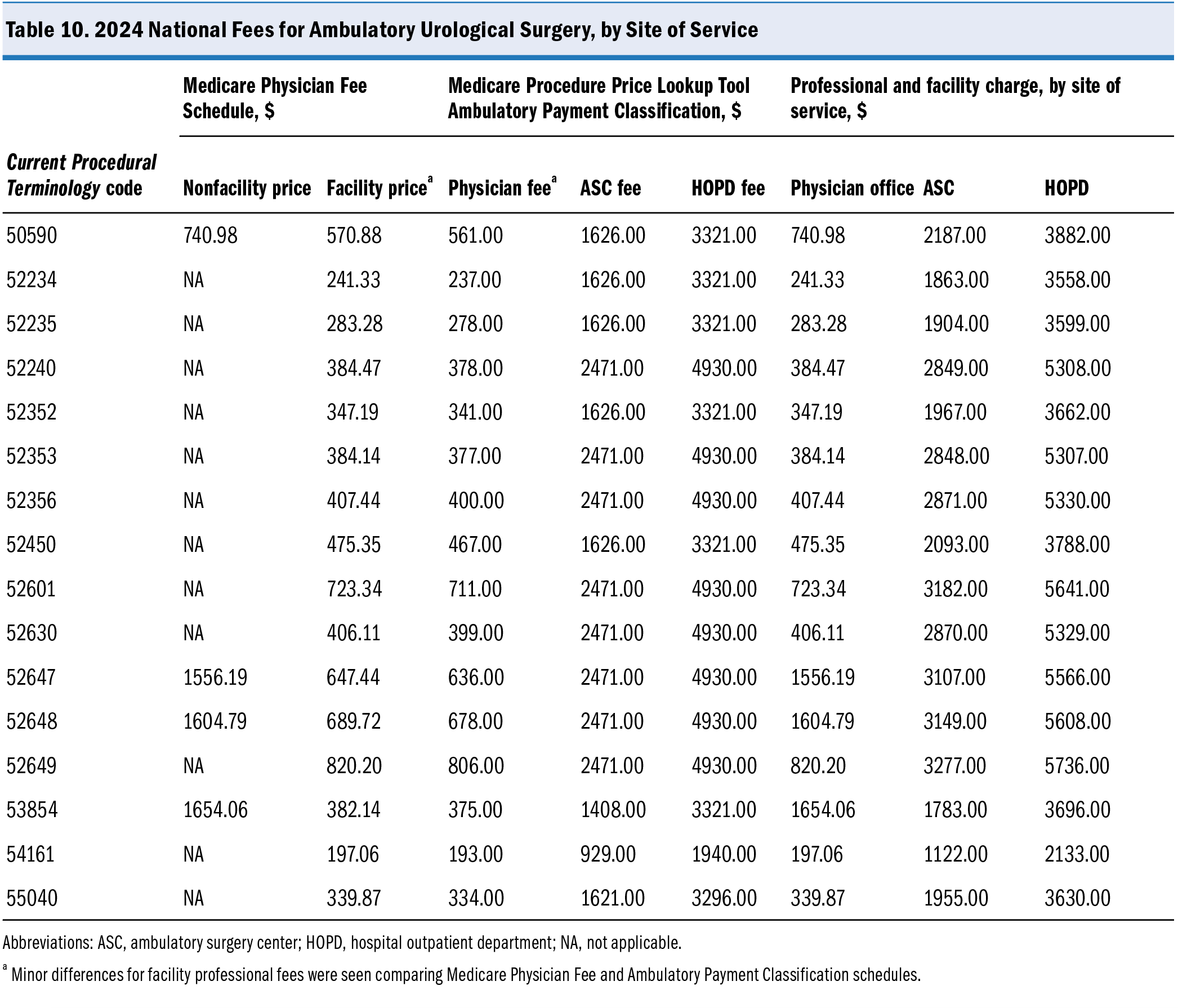

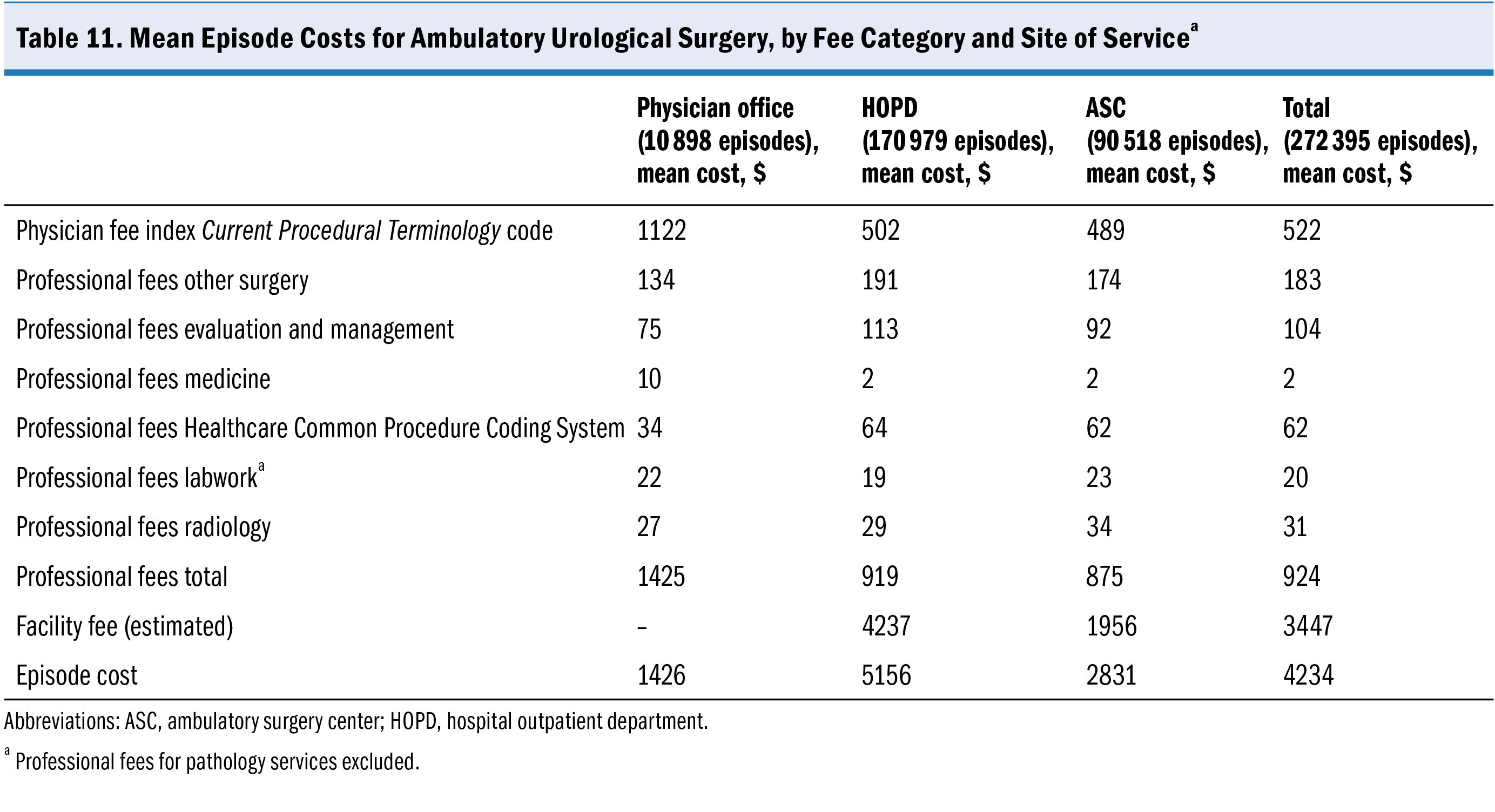

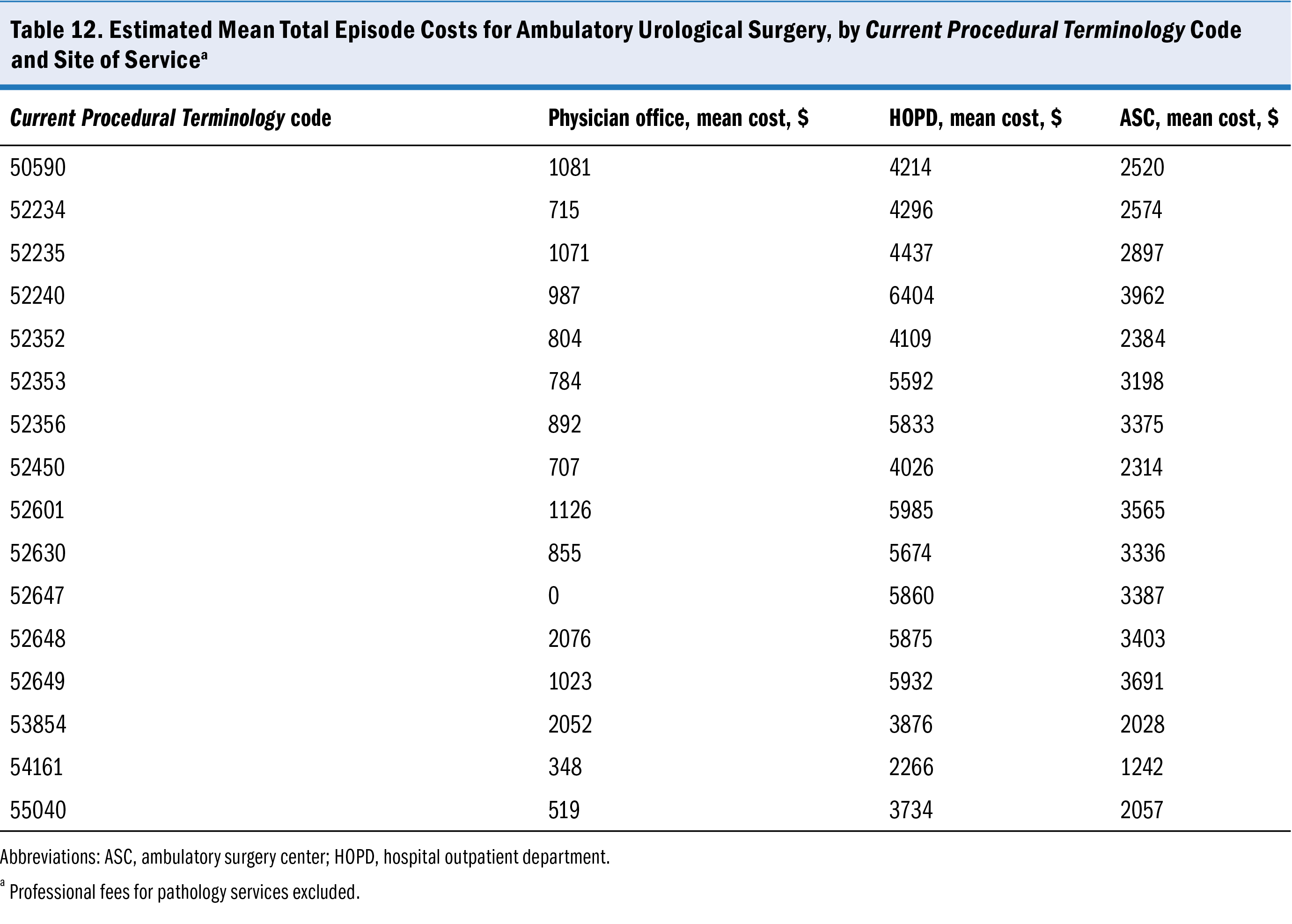

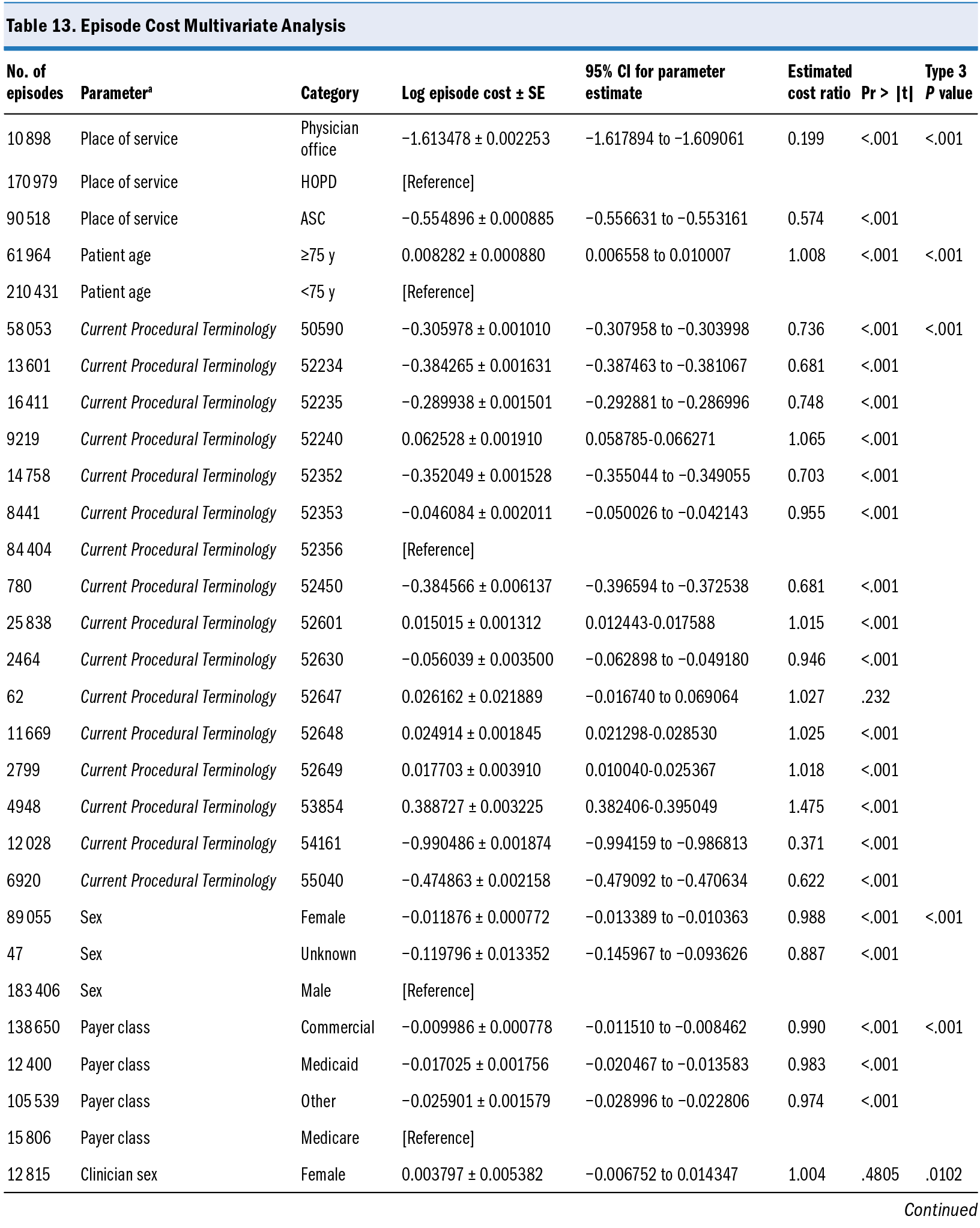

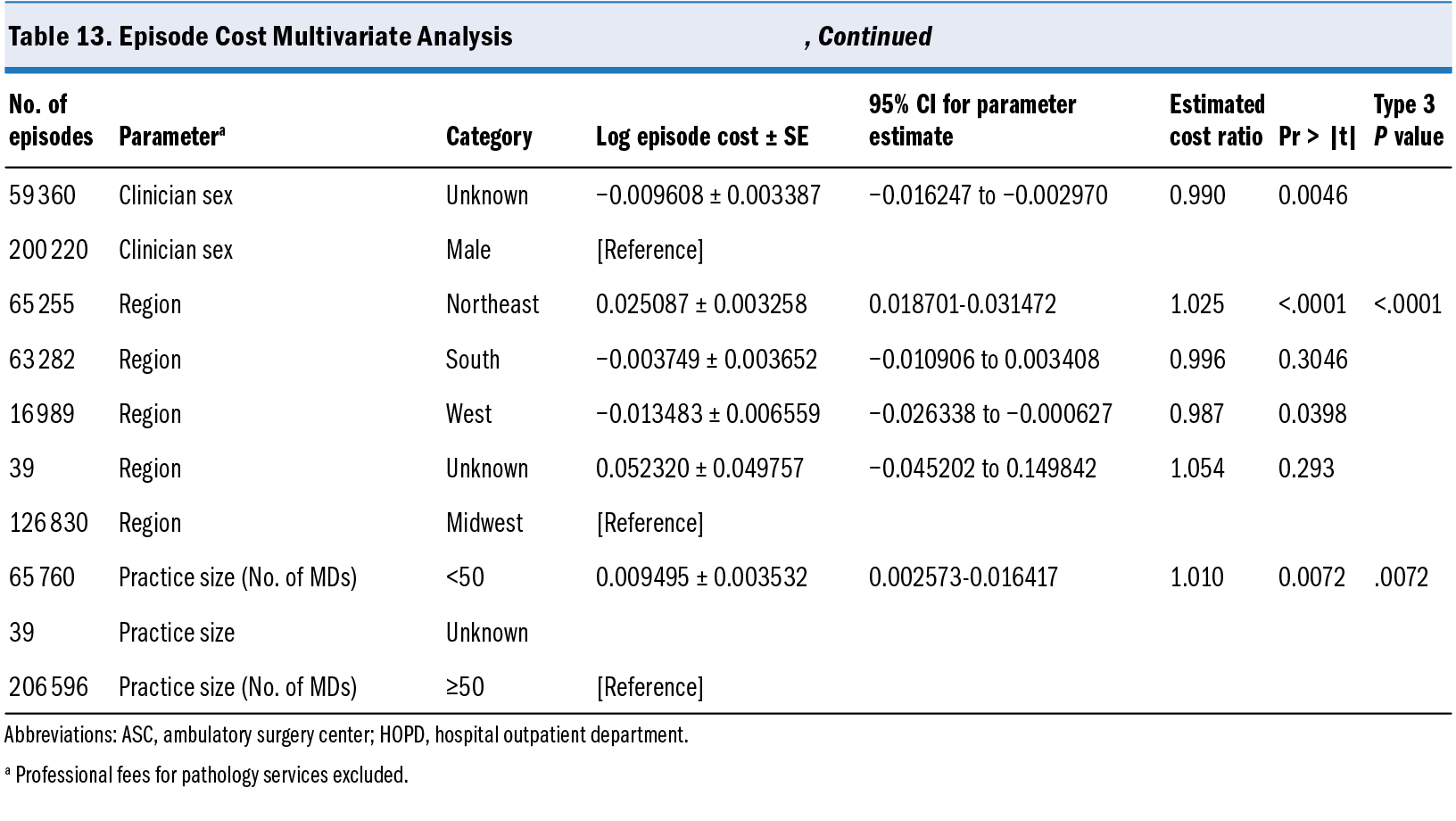

Relative cost was calculated by using the actual year-specific Medicare allowable charges for all professional services in an episode, and then applying the 2024 national fee information for facility charges to the actual data. Medicare pays more for a given procedure when it is performed in an HOPD (under the Outpatient Prospective Payment System) than in an ASC or a physician office (Table 10). Mean episode costs for all procedures performed in an HOPD were $5156 vs $2831 for ASC and $1426 for a physician office; although there were small differences in professional fees by site of service, facility costs accounted for most of the difference in total cost (Table 11). Costs by site of service are seen in sharp relief at the procedure level (Table 12).

Multivariate analysis confirmed the statistical significance of differences in total episode cost by site of service after adjusting for other variables (Table 13). Compared with an HOPD and after adjusting for other covariates, the estimated cost ratio for procedures done in an ASC was 0.57 and 0.20 for procedures done in a physician office. Other statistical differences in cost were seen by practice region (higher costs in Northeast, P < .001), size of practice (higher costs in smaller practices, P = .0072), patient age (higher costs in patients 75 years of age and older, P < .001), patient sex (higher cost in male patients,

P < .001), and payer class (higher cost in Medicare,

P < .001).

Discussion

This large study of community urology practice patterns confirms that common stone, prostate, and genital surgical procedures are usually performed in the outpatient setting (92% of the procedures selected for this analysis), with low rates of adverse outcomes. Medicare and other insurers pay significantly more for the same procedures performed in an HOPD than in a physician office or ASC, with no demonstrated benefit for this additional cost. The current analysis helps quantify these differences—most of which are secondary to the facility fee alone—and reaffirm existing findings in the literature, which show lower costs in the ASC or physician office setting.8 This study did not find evidence that lower procedural costs in the ASC or office setting led to higher utilization costs of professional services in the first postoperative 90 days. Moreover, this study showed that ED visits, hospital visits or admissions, catheterizations, and complication billing codes were significantly more likely after a procedure performed in the more expensive HOPD setting than in the less expensive ASC or physician office setting. These findings compare favorably with those of other similar studies: The current study’s unadjusted overall rate of ED visits and hospital visits following stone procedures (6.6%) is nearly identical to that documented by Michel et al9 in their examination of ambulatory surgery for kidney stones (6.4%); the combined ED visit rate of 0.28% for the current study’s 16 procedures is much lower than in a similar study by Witherspoon10 of outpatient surgery in Canada (16%); our study’s ED visit and hospital visit rates for this entire set of procedures are slightly higher (5.51%) than that of a study by Rambachan et al11 (3.7%) examining “readmissions” (our study counted outpatient and inpatient visits in its metric). The current study also adds to the body of literature regarding outpatient surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. In a meta-analysis of 20 studies of outpatient benign prostatic hyperplasia surgery, Salciccia et al5 found an overall event rate for postoperative complications and early postoperative visits of almost 19%; the current study’s work showed an overall event rate of 16.44% (ED visits, 0.18%; hospital visits, 8.02%; and catheterizations, 6.24%) (Table 5). In summary, our work supports that of other authors, who have found that many urologic procedures can be performed safely in an ASC or physician office with outcomes and costs that are favorable compared with the HOPD setting.3,5,12 Although our study did find significant associations between outcomes and certain patient and clinician characteristics, these findings were inconsistent across those outcomes and not directly comparable with previous studies. This study has important implications for patients, clinicians, payers, and policymakers. Because the most common insurance paradigm (including fee-for-service Medicare) involves patient co-insurance, a patient may face substantially higher out-of-pocket costs if a procedure is performed at an HOPD rather than at an ASC or a physician office. The study furthermore found that adverse outcomes were 1.2 to 3 times more likely if these procedures were performed in an HOPD vs an ASC. It was not possible to capture or estimate the cost of these outcomes beyond the urologists’ professional fees, but they are believed to be substantial. For example, an ED visit after a stone procedure would likely involve professional fees from the ED physician and radiologist, facility fees for radiology and supplies, intravenous fluids and medications, and perhaps even hospital admission. The finding that complication billing codes were appended to encounters following procedures done in an HOPD at a higher rate than those done in an ASC has implications for patients in Medicare Advantage programs, where charges and payments are often linked to measures of disease “severity” supported by these codes. Finally, the payment differential between an HOPD and other ambulatory settings has other consequences that can exacerbate the financial impact to the health care system. For example, hospitals may be incentivized by the current payment schedule to shift care from an ASC (joint venture) to the HOPD or to acquire practices for that purpose. For all these reasons the study’s approximations of relative cost differences—and the potential for cost savings with policy changes—are probably underestimates.

This study has limitations. The choice of procedures included in this analysis may have produced results that are not generalizable to other outpatient procedures. Some urology practices are able to offer surgical procedures in the office setting while others are not, and clinician access to an ASC is not equal across practice settings; it was not possible to identify or control for these structural differences in the analysis. We had no access to clinical comorbidities, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, or other measures of patient acuity that could contribute to patterns of utilization of hospital sites. International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes signifying complications may be used differently by different physicians and may not always indicate a true clinical condition. The study’s data cannot be used to determine actual costs or compare costs across different payers. Claims data outside the urology practice were not accessible, so assumptions about relative facility costs based on Medicare’s Ambulatory Payment Classification system were made; actual costs of ED visits, hospital visits, and nonurologic care were unknown.

Conclusions

Many urologic procedures can be safely performed in the ambulatory setting. This large study based on real-world evidence suggests that the physician office or ASC is a safer and less expensive setting for common outpatient urologic procedures compared with the HOPD. This study may assist policymakers and other stakeholders concerned with reforming payment systems to improve outcomes and reduce costs.

References

1. Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;(11):1-25.

2. Aligning fee-for-service payment rates across ambulatory settings. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2022:161-187. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Jun22_MedPAC_Report_to_Congress_v4_SEC.pdf

3. Hollingsworth JM, Saigal CS, Lai JC, Dunn RL, Strope SA, Hollenbeck BK; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Surgical quality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing outpatient urological surgery. J Urol. 2012;188(4):1274-1278. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.031

4. Patel HD, Matlaga BR, Ziemba JB. Trends in the setting and cost of ambulatory urological surgery: an analysis of 5 states in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Urol Pract. 2019;6(2):79-85. doi:10.1016/j.urpr.2018.05.001

5. Salciccia S, Del Giudice F, Maggi M, et al. Safety and feasibility of outpatient surgery in benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endourol. 2021;35(4):395-408. doi:10.1089/end.2020.0538

6. Medicare Procedure Price Lookup for Outpatient Services. Medicare. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup/

7. Physician Fee Schedule Lookup Tool. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search/overview

8. Hollingsworth JM, Saigal CS, Lai JC, Dunn RL, Strope SA, Hollenbeck BK; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Medicare payments for outpatient urological surgery by location of care. J Urol. 2012;188(6):2323-2327. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.031

9. Michel KF, Patel HD, Ziemba JB. Emergency department and hospital revisits after ambulatory surgery for kidney stones: an analysis of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Urolithiasis. 2021;49(5):433-441. doi:10.1007/s00240-021-01252-8

10. Witherspoon L, Breau RH, Langley C, et al. Returning to the emergency room: an analysis of emergency encounters following urological outpatient surgery. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15(10):333-338. doi:10.5489/cuaj.7063

11. Rambachan A, Matulewicz RS, Pilecki M, Kim JYS, Kundu SD. Predictors of readmission following outpatient urological surgery. J Urol. 2014;192(1):183-188. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.053

12. Suskind AM, Dunn RL, Zhang Y, Hollingsworth JM, Hollenbeck BK. Ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient urologic surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Urology. 2014;84(1):57-61. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.04.008

Article Information

Published: December 13, 2024.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Dowling is a paid consultant to LUGPA, Dr Goldfischer is the president of LUGPA, and Dr Albala is a LUGPA board member. LUGPA is nonprofit urology trade association whose mission is to preserve and advance the independent practice of urology.

Funding/Support: Funding and support for the research of this article was provided by LUGPA.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed equally to this article’s creation.

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from LUGPA, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are therefore not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of LUGPA.

Acknowledgments: The following collaborators are recognized for their contributions to this manuscript by critical review of the study proposal, acquisition of funding, and collection of data: Kirsten Anderson; David Carpenter; David Ellis, MD; Jason Hafron, MD; Jonathan Henderson, MD; Mara Holton, MD; Celeste Kirschner; Benjamin Lowentritt, MD; David Morris, MD; Timothy Richardson, MD; Cass Schaedig; Scott Sellinger, MD; and Jeffrey Spier, MD.