Introduction

We are faced with tremendous challenges in the existing US health care infrastructure, from the question of sustainability to variances in and hindrances to access, spiraling costs, and growing workforce shortages. Effective solutions will require an honest and comprehensive accounting of the reality of how care has evolved and how it can be and is delivered in the existing labyrinthine system. Rather than wishing for a long-ago time, when there was no “business of medicine,” it is essential that we contextualize our analysis with an understanding that health care professionals are—and should be—involved both in care and in the business of care.

The physician and the health care administrator roles and responsibilities must function in tandem to achieve the goals of effective, efficient, and sustainable health care delivery. Both positions require undergraduate and postgraduate education (medical school for the physician and graduate school in business or health care administration for the administrator), followed by postgraduate training (a specialty-specific residency for the physician and an administrative residency or fellowship offered through various health care organizations for the administrator). In some instances, both professionals may pursue further subspecialties in their respective disciplines. The ability of these professionals to achieve lasting results is the outcome of the countless hours spent honing their skills and craft. Malcolm Gladwell’s 10 000-hour rule of mastery1 is probably the best approximation of the time required for physicians and administrators to reach the level of proficiency the country’s health care system now requires.

For the independent practice as a microcosm of the entire health care industry, the COVID-19 pandemic can be equated to a category 5 hurricane that ran across the entire country and back again, leaving devastation in its wake. The most recent wave of cyberattacks against health care institutions, including hospitals, insurance companies, and practices, are another hurricane that the industry is currently experiencing, with no end in sight or full understanding of the level of impact. Independent practices and the field of medicine have risen to meet their share of challenges. Those challenges have been met because of the social contract that physicians and health care workers have with patients, families, and communities—a social contract that works in both directions.

In the daily work of ethically growing a health care business while managing costs, physicians and administrators cannot forget the mental health of the practice’s workforce, themselves included. Delivering care to the community with the unintentional outcome of self-harm is a pitfall that should diligently be evaluated on the personal and corporate levels. Burnout in health care is a major challenge, one that is growing and affecting the effectiveness of care delivery. For the independent practice, including the physician and the administrator, the daily challenges beyond revenues and costs are myriad, but the practice and the business of medicine are rewarding and worth continuing.

Abbreviations

EHR electronic health record

MPFS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule

The intertwining of the physician’s and the administrator’s areas of expertise in providing a sustainable service was on full display during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the years immediately following it. The pandemic highlighted and exacerbated the unequal playing field between different care entities within the health care industry and independent practices.2 Sustaining the delivery of independent medical and surgical services during and after the COVID-19 pandemic was a challenge for physicians and administrators in 2 foundationally acute areas: growing revenue and managing costs.

Growing Revenue

In business, there is the understanding that if the enterprise is not growing, it is dying.3 In rudimentary financial terms: Revenue must exceed costs to a level that the business can reinvest to continue to grow. How the business grows year over year is the daily conundrum of the physician and administrator. As Peter Drucker famously stated, “innovate or die.”4 This philosophy drives the mergers-and-acquisitions mindset that has catalyzed the growth of large, vertically integrated organizations in all sectors of the US health care industry. A practice must look each year to how it generates revenue for the services it provides to its customers: the patients. Financially, patients are categorized as individuals without insurance or who self-pay, individuals with commercial insurance, and individuals covered by Medicare or Medicaid. These patients may need the same services, but the practice receives payment through vastly different mechanisms for each group. For simplicity, the focus for the remainder of this article will be on individuals whose care is paid for in part or whole by Medicare or Medicaid.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Medicare system were created in 1965 and will celebrate their 60th anniversary in 2025.5 Medicare and Medicaid were designed to ensure that individuals 65 years of age and older and low-income individuals, respectively, had access to health care. Each business entity in health care has its own associated fee schedule or method of payment from Medicare. The payment method is one in which the entity is paid for the service provided, not necessarily the outcome obtained. Paying for volume is not necessarily a negative for society because the free market will course-correct and remove health care professionals or practices that are not producing consistent outcomes. Medicare and Medicaid fee schedules have gradually become the de facto benchmark for all health insurance products’ fee schedules or payment mechanisms over the past 59 years. In essence, although all health care is delivered locally, the United States has a complex single-payor system that has a direct influence on the revenues a practice can earn by providing services to 2 of the 3 customer categories.

The primary payment mechanism for independent practices in urology is the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The MPFS is a misnomer. The nomenclature of the MPFS implies that any payment made under the system goes directly to the physician; it does not. It goes to the corporate entity that employs the physician and staff who deliver the care. During the past more than 30 years, costs to deliver care have steadily increased, while reimbursement fees have either stagnated or decreased.6 The only real direct mechanism a practice has to maintain its ability to provide services to the community is to see more patients, thereby generating additional revenue to subsidize the increasing costs. In the face of decreasing revenue per service provided, the independent practice is left with difficult ethical decisions regarding the who, what, when, and how of providing services to the community in this post–COVID-19 environment.

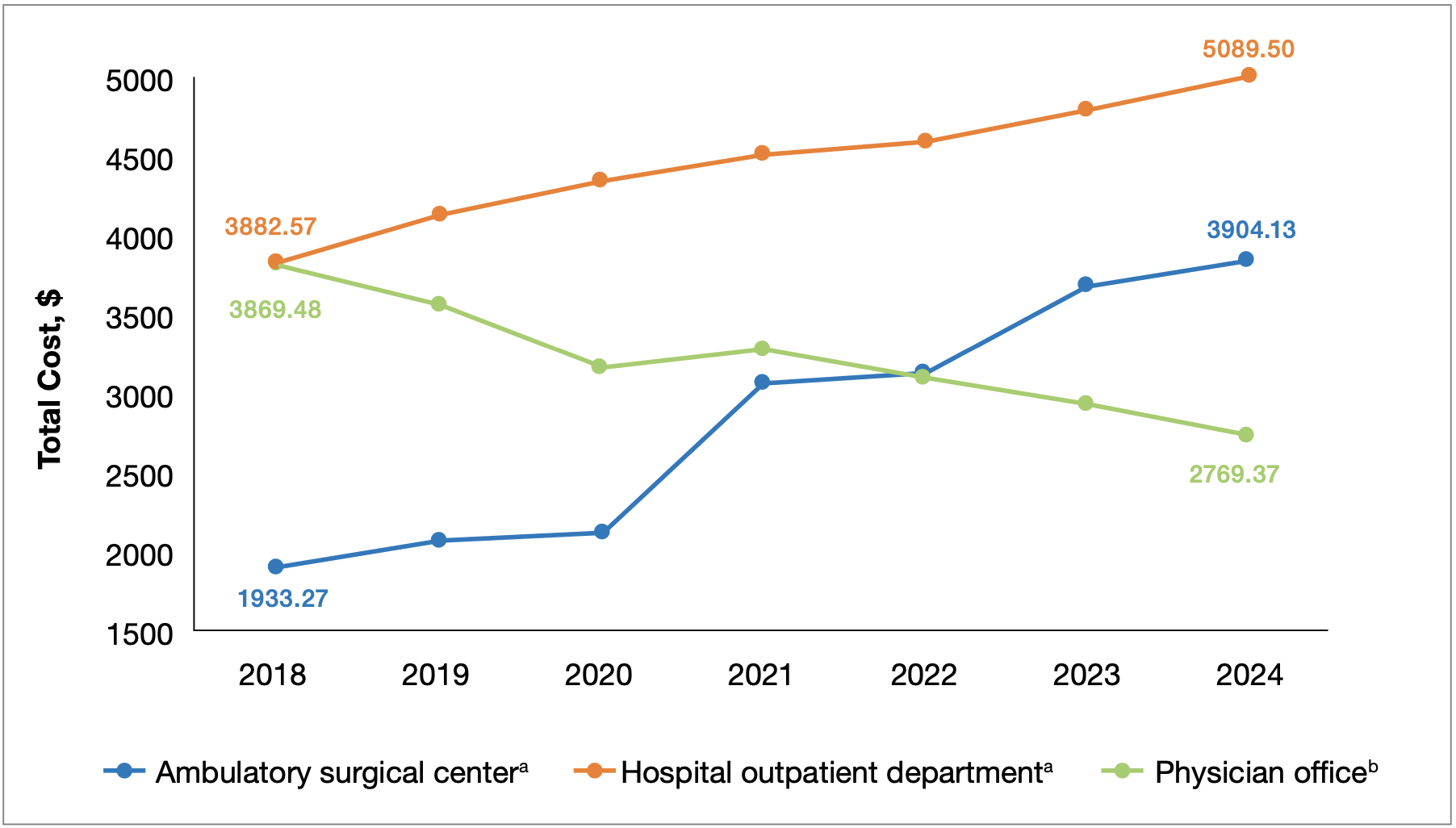

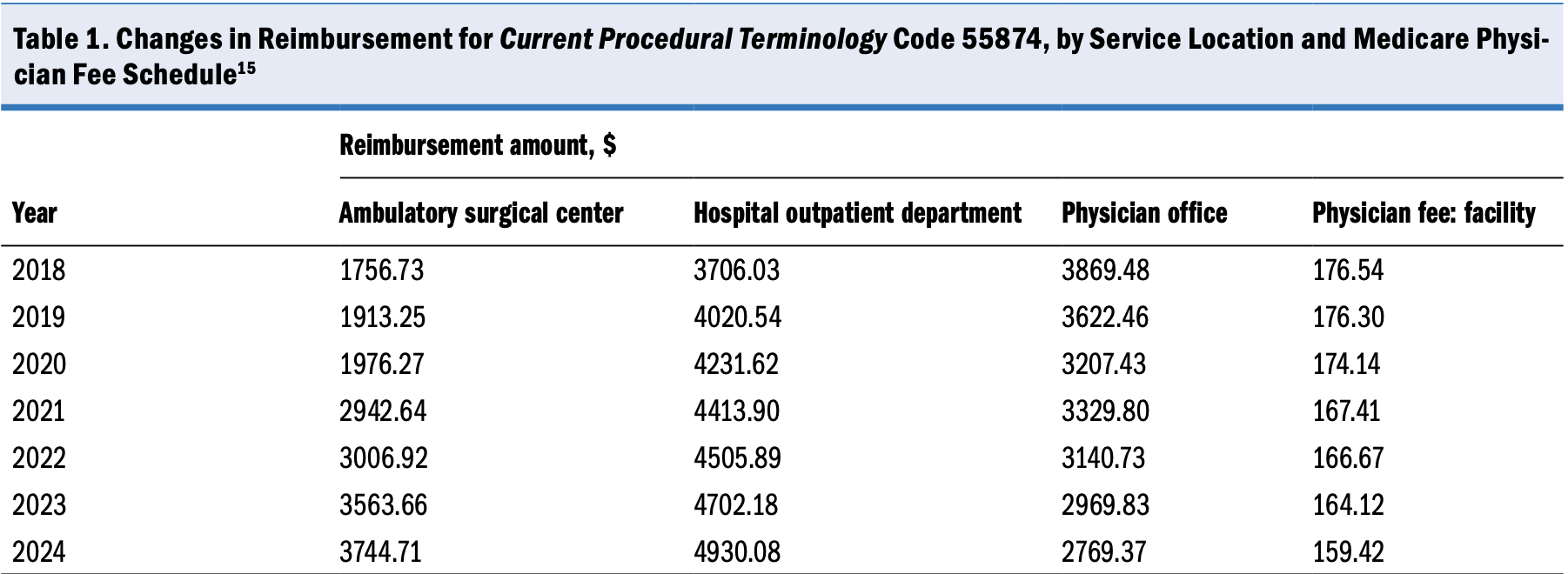

A microcosm of this challenge in independent urology practices can be found in physician practice reimbursement for the placement of hydrogel (Current Procedural Terminology code 55874) over the past 7 years (Figure 1 and Table 1). Hydrogel was launched as an innovative product that could help mitigate the severity and likelihood of certain rectal adverse effects of radiation therapy for patients with prostate cancer. This novel therapy could be provided in 3 locations: the hospital outpatient department, the ambulatory surgical center, or the physician practice.

Figure 1. Total cost of care for Common Procedural Terminology code 55874, by service location15

a Does not include anesthesia services because of variability by service location.

b Rates reflected are based on the initial rates published during each calendar year.

The equipment needed to deliver this care is uniform, regardless of service location. For independent practices, hydrogels represented a new service that could generate a procedural revenue stream at a lower cost to patients. Over the past 7 years, however, hydrogel reimbursement in the practice setting has declined, while practice expenses have been subject to an inflationary increase representing a real pay reduction of more than one-third to the practice. This situation poses an unfortunate ethical challenge to the physician and administrator: perform more procedures to maintain revenue in the physician practice setting, stop performing the procedure in question, or move the procedure to a facility where the insurer and patient will ultimately pay more for the service but the practice will be required to subsidize the roughly 10% pay cut rather than the full 33%. Sadly, the example of hydrogel is not an isolated event but the norm across the entire MPFS and other fee schedules.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a loosening of the regulatory environment, which led to advances in the way care was delivered, including broader use of remote health care services incorporating medication delivery and telemedicine. In the post–COVID-19 environment, these advances in care have been shuttered by the return of prepandemic regulations that have stunted practices’ ability to compete with other health care service entities and innovate ways to deliver care. Most notable is the return of the requirement for practices that have an in-office dispensary to have their patients come into the office to pick up their medications instead of being able to mail them to the patient’s location. During the pandemic, practices were able to mail prescriptions to patients, thereby delivering patients the care they need in their home. Now, practices must either require the patient to come to the office or send the medication to a mail-order pharmacy and give up the opportunity to provide a service and be compensated for it. Both options have a negative impact on the practice and the patient. Further complicating the matter are potential mail delays that can affect a patient’s ability to remain adherent on a medication, which may lead to additional health issues for the physician to address.7

Practices face the ethical challenge of which services to provide based on the health outcomes they bring to the patient, the resources needed to provide these services, and the financial margin the practice attains through them. Providing a service that generates a margin but does not improve the patient’s health goes against the “first, do no harm” ethos. Stark law and other regulations further inhibit physician practice innovation and sustainable growth. Growing diverse revenue streams in the face of the regulatory environment is the daily focus of the practice striving to sustain and promote its ability to meet its mandate of caring for the community.

Managing Costs

All health care entities are for-profit entities; the only difference is their tax structure and thus their nomenclature. Fundamentally, these are all businesses with coincident obligations, including care for patients as well as careful stewardship of business resources and costs. In business schools across the country, the old joke is often told in accounting, finance, and strategy courses: We lose money on every sale, but don’t worry; we will make it up in volume. Insolvency is the fastest way to extinction. For each service the practice delivers to the patient, it is imperative that the service, at minimum, breaks even from an accounting perspective, or it will inevitably consume the practice.

From a purely business perspective, resources are developed, cultivated, and carefully stewarded because they are scarce. Conversely, costs are, at worst, to be consistently maintained or, at best, to be continuously reduced. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the scarcity of engaged and competent health care workers who would walk into environments filled with the sickest patients daily. The 100-year-old institutional battles among hospitals, practices, skilled nursing facilities, and ambulatory surgical centers were brought to the forefront during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The independent practice has advantages over the hospital or health system in that it can be nimbler in its utilization and cultivation of the health care workforce. The hospital or health system has the economic advantage of being able to pay more for the same health care worker than the independent practice because of the unequal reimbursement system in the United States.8 During the various peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not uncommon for hospitals to reassign their employed physician, nurse, and medical assistant resources to intensive care units, where those workers may not have been fully trained to provide the care the community expected.9,10 In 2021, the nursing workforce contracted by more than 100 000 people compared with the previous year, and the vast majority of people in the field saw circumstances continuing on a negative trend before anything would improve.11 For the physician and administrator of the independent practice, the ethical challenge is balancing staffing needs in the face of declining reimbursement and increased competition for those staff.

As a result of any number of technological advancements and regulatory requirement changes, the overhead costs of care delivery have risen precipitously in recent decades, exemplified by the costs required for information technology and electronic health record (EHR) systems over the past 5 years. In the independent setting (MPFS), this increase in costs has occurred alongside a sharp decline in reimbursement.12 From a regulatory standpoint, there is no difference in the requirements that a hospital or an independent practice are held to with regard to protecting patients’ information. The regulatory burden for practices is equal to that of hospitals and insurance companies, but the payments and funding available to meet that regulatory burden disproportionately favors health systems and insurance providers.

Electronic health records and information technology are both powerful tools that can help practices become more efficient. Investing in information technology and EHR systems can improve efficiency within the office. For example, an interface between the practice’s urinalysis machine and EHR system can reduce human errors in data transfer, provide data to the surgeon or advanced practice professional in real time, and allow for structured data that can be tracked as part of the patient’s records. Most EHR systems, however, do not have that interface with the urinalysis machine as a standard feature; it is something the practice will have to invest in creating. This interface will cost the practice money in the development phase, the maintenance phase, and every time there is a software upgrade for either the EHR system or the urinalysis machine. All this would have to be paid for as a component of the declining amount reimbursed for the global office visit because Medicare is no longer reimbursing for the simple urinalysis (Current Procedural Terminology code 81003).13 The challenges at hand are the increasing regulatory burden, the increasing costs of technology, and the decreasing reimbursement to fund the first 2 challenges.

Independent practices are facing ethical challenges every day in how to continue to deliver care in the face of ever-increasing costs and competition for critical resources. With the rising costs for and decreasing supply of health care workers, practices are left with challenging decisions regarding which services they can provide to the community. Policy makers want to create 1-size-fits-all solutions at the national level, but it is in our communities’ best interest to have those decisions made locally by physician and administrator leaders.

Conclusions

Primum non nocere—“First, do no harm”—is the responsibility of not only the physician but also the professional administrator, according to Peter Drucker.14 Despite this responsibility, health care is the most complex and regulated business in the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic elicited a brief positive sentiment toward those who work in health care and even recognition that “not all heroes wear capes.” In the post–COVID-19 environment, however, the pendulum of public opinion has swung back. It is in the best interest of society to remember that health care workers and independent practices are resources to be developed, not costs to be minimized.

References

1. Gladwell M. The 10,000-Hour Rule. Outliers The Story of Success. Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

2. News articles about the importance of independent practice and the threats they face. LUGPA. 2024. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.lugpa.org/importance-of-independent-practice

3. Schellinger M. In business, you’re either growing or you’re dying. Forbes. March 23, 2018. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeslacouncil/2018/03/23/in-business-youre-either-growing-or-youre-dying/?sh=32e5fdd4400d

4. Ignatius A. Innovation on the fly. Harvard Business Review. December 2014. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://hbr.org/2014/12/innovation-on-the-fly#:~:text=The%20origin%20of%20the%20phrase,has%20the%20resources%20or%20%5B%E2%80%A6%5D

5. History. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated September 6, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/about-cms/who-we-are/history

6. Resneck J Jr. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. American Medical Association. October 3, 2022. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

7. Cubanski J, Fuglesten Biniek J, Rae M, Damico A, Frederiksen B, Salganicoff A. Mail delays could affect mail-order prescriptions for millions of Medicare Part D and large employer plan enrollees. Kaiser Family Foundation. August 20, 2020. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/mail-delays-could-affect-mail-order-prescriptions-for-millions-of-medicare-part-d-and-large-employer-plan-enrollees/

8. Peterson L. Hospitals are raising pay to combat the health care worker shortage. BenefitsPro. December 20, 2023. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.benefitspro.com/2023/12/20/hospitals-are-raising-pay-to-combat-the-health-care-worker-shortage/?slreturn=20240530-32410

9. Hundreds of nurses reassigned to meet COVID-19 needs. Cedars Sinai. February 8, 2021. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.cedars-sinai.org/newsroom/hundreds-of-nurses-reassigned-to-meet-covid-19-needs/

10. Simpson BB, Whitt MO, Berger L. Patient care services staffing support during a pandemic. Nurse Leader. 2021;19(2):150-154. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2020.07.005

11. Morris G. Survey says: nurses are likely to leave the profession. Nurse Journal. October 10, 2023. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://nursejournal.org/articles/nurses-leaving-the-profession/

12. MGMA Staff Members. Measuring the rising costs of health IT compliance in medical groups. Medical Group Management Association. March 16, 2023. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/mgma-stats/measuring-the-rising-costs-of-health-it-compliance-in-medical-groups

13. Physician’s Fee Schedule Code Search & Downloads. Novitas Solutions. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/portal/MedicareJL/FeeLookup

14. Drucker PF. Post Capitalist Society. 1st ed. HarperBusiness; 1993.

15. Prospective payment systems—general information. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. Updated November 15, 2023. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/prospective-payment-systems

Article Information

Published: September 13, 2024.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support: None.

Author Contributions: The authors contributed equally to this article.

Data Availability Statement: All data sources are in the public domain.

Citation: Diller NP, Holton M. The business of independent urologic medicine: caring for patients while operating a business in a post–COVID-19 era of private practice. Rev Urol. 2024;23(3):e83-e88.

Corresponding author: Nathan P. Diller, MBA, MHSA, CMPE, FACHE, Brandywine Urology Consultants, 2000 Foulk Rd, Ste F, Wilmington, DE 19810 (ndiller@brandywineurology.com)